A study on batteries

Choosing what battery to use is driven by several conditions which should be taken into consideration before making a choice. Here come some of them.

* Battery cycle life is defined as the number of complete charge - discharge cycles a battery can perform before its nominal capacity falls below 80% of its initial rated capacity. “Lifetimes of 500 to 1200 cycles are typical. An alternative measure of cycle life is based on the internal resistance of the cell. In this case the cycle life is defined as the numer of cycles the battery can perform before its internal resistance increases by an agreed amount., usually 1.3 times or double its initial value when new.”[4][6][1].

* “Battery shelf life is the time an inactive battery can be stored before it becomes unusable, usually considered as having only 80% of its initial capacity as above.”[1]

* Battery calendar life is the elapsed time before a battery becomes unusable whether it is in active use or inactive as above.

Cycle life

[4][1][6]

The effects of voltage and temperature on cell failures tend to be immediately apparent, but their effect on cycle life is less obvious. The noncompliance with the recommended operating window is reported to cause irreversible capacity loss in the cells. “The cumulative effect of these digressions is like having a progessively debilitating disease which affects the life time of the cell or in the worst case causes sudden death if you overstep the mark.” [3]

“The graph above shows that starting at about 15 ºC cycle life will be progressively reduced by working at lower temperatures. Operating slightly above 50 ºC also reduces cycle life but by 70 ºC the threat is thermal runaway. The battery thermal management system must be designed keep the cell operating within its sweet spot at all times to avoid premature wear out of the cells.” [4]

Temperature effects

Chemicals reactions are led by either voltage or temperatures. Mathematically, these effects could be demonstrated by the following equation, which is called Arrhenius equation. [1][4][3][6]

“In which A is the pre-exponential factor or simply the prefactor and R is the gas constant. The units of the pre-exponential factor are identical to those of the rate constant and will vary depending on the order of the reaction. If the reaction is first order it has the units s−1, and for that reason it is often called the frequency factor or attempt frequency of the reaction. Most simply, k is the number of collisions that result in a reaction per second, A is the total number of collisions (leading to a reaction or not) per second and is the probability that any given collision will result in a reaction. Therefore, the Arrhenius equation defines the relationship between temperature and the rate at which a chemical action proceeds. It shows that the rate increases exponentially as temperature rises. As a rule of thumb, for every 10 °C increase in temperature the reaction rate doubles. Thus, an hour at 35 °C is equivalent in battery life to two hours at 25 °C. Heat is the enemy of the battery and as Arrhenius shows, even small increases in temperature will have a major influence on battery performance affecting both the desired and undesired chemical reactions. As an example of the importance of storage temperature conditions - Nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) chemistry in particular is very sensitive to high temperatures. Testing has shown that continuous exposure to 45°C will reduce the cycle life of a I-MH battery by 60 percent and as with all batteries, the self discharge rate doubles with each 10°C increase in temperature.”[4]

“The graph below shows how the life of high capacity tubular Ironclad Lead Acid batteries used in standby applications over may years varies with the operating temperature. Note that running at 35 °C, the batteries will deliver more than their rated capacity but their life is relatively short, whereas an extended life is possible if the batteries are maintained at 15 °C.”[4]

“Chemical reaction rates decrease in line with temperature. The effect of reducing the operating temperature is to reduce rate at which the active chemicals in the cell are transformed. This translates to a reduction in the current carrying capacity of the cell both for charging and discharging. In other words its power handling capacity is reduced. Futhermore, at low temperatures, the reduced reaction rate (and perhaps contraction of the electrode materials) slows down, and makes more difficult, he insertion of the Lithium ions into the intercalation spaces. As with over-voltage operation, when the electrodes cannot hold the current flow, the result is reduced power and anode plating with irreversible capacity loss.” [4]

“Apart from the gradual deterioration of the cell over time, under conditions of abuse, temperature effects can lead to premature failure of the cell. This can happen even under normal operating conditions if the rate of heat generated in the battery exceeds the rate of heat loss to the environment. In this situation the battery temperature will continue to rise leading to a condition known as thermal runaway which ultimately results in disastrous consequences. Several stages are involved in the build up to thermal runaway and each one results in progressively more permanent damage to the cell. 1. The first stage is the breakdown of the thin passivating SEI layer on the anode, due to overheating or physical penetration. The initial overheating may be caused by excessive currents, overcharging or high external ambient temperature.The breakdown of the SEI layer starts at the relatively low temperature of 80ºC and once this layer is breached the electrolyte reacts with the carbon anode just as it did during the formation process but at a higher, uncontrolled, temperature. This is an exothermal reaction which drives the temperature up still further. (Lithium Titanate anodes do not depend on an SEI layer and hence can be used at higher rates.)

2. As the temperature builds up, heat from anode reaction causes the breakdown of the organic solvents used in the electrolyte releasing flammable hydrocarbon gases (Ethane, Methane and others) but no Oxygen. This typically starts at 110 ºC but with some electrolytes it can be as as low as 70ºC. The gas generation due to the breakdown of the electrolyte causes pressure to build up inside the cell. Although the temperature increases to beyond the flashpoint of the gases released by the electrolyte the gases do not burn because there is no free Oxygen in the cell to sustain a fire.

3. The cells are normally fitted with a safety vent which allows the controlled release of the gases to relieve the internal pressure in the cell avoiding the possibility of an uncontrolled rupture of the cell - otherwise known as an explosion or more euphemistically “rapid disassembly” of the cell. Once the hot gases are released to the atmosphere they can of course burn in the air.

a. At around 135 ºC the polymer separator melts, allowing the short circuits between the electrodes.

b. Eventually heat from the electrolyte breakdown causes breakdown of the metal oxide cathode material releasing Oxygen which enables burning of both the electrolyte and the gases inside the cell. The breakdown of the cathode is also highly exothermic sending the temperature and pressure even higher. The cathode breakdown starts at around 200 ºC for Lithium Cobalt Oxide cells but at higher temperatures for other cathode chemistries.

By this time the pressure is also extremely high, so it is too hazardous to stay near the battery.”[4]

Pressure effects

These problems relate to sealed cells only[3]. Increased internal pressure within a cell is usually due to increased temperature. Both temperature and pressure effect may be caused by several factors. Excessive currents or a high ambient temperature will cause the cell temperature to rise and the resulting expansion of the active chemicals will in turn cause the internal pressure in the cell to rise. Overcharging also causes a rise in temperature, but more seriously, overcharging can also cause the release of gases resulting in an even greater build up in the internal pressure.

Unfortunately increased pressure tends to magnify the effects of high temperature by increasing the rate of the chemical actions in the cell, not just the desired Galvanic reaction but also other factors such as the self discharge rate or in extreme cases contributing to thermal runaway. Excessive pressures can also cause mechanical failures within the cells such as short circuits between parts, interruptions in the current path, distortion or swelling of the cell case or in the worst case actual rupture of the cell casing. All of these factors tend to reduce the potential battery life.[4][3]

====Depth Of Discharge (DOD)====[3] [4] “At a given temperature and discharge rate, the amount of active chemicals transformed with each charge - discharge cycle will be proportional to the depth of discharge. The relation between the cycle life and the depth of discharge is logarithmic as shown in the graph below. In other words, the number of cycles yielded by a battery goes up exponentially the shallower the DOD. This holds for most cell chemistries.

Cycle life Vs. Depth of discharge

(The curve just looks like a logarithmic curve. It is actually a reciprocal curve drawn on logarithmic paper). The above graph was constructed for a Lead acid battery, but with different scaling factors, it is typical for all cell chemistries including Lithium-ion. This is because battery life depends on the total energy throughput that the active chemicals can tolerate. Ignoring other ageing effects, one cycle of 100% DOD is roughly equivalent to 2 cycles at 50% DOD and 10 cycles at 10% DOD and 100 cycles at 1% DOD.

There are important lessons here both for designers and users. By restricting the possible DOD in the application, the designer can dramatically improve the cycle life of the product. Similarly the user can get a much longer life out of the battery by using cells with a capacity slightly more than required or by topping the battery up before it becomes completely discharged. For cells used for “microcycle” applications (small current discharge and charging pulses) a cycle life of 300,000 to 500,000 cycles is common.

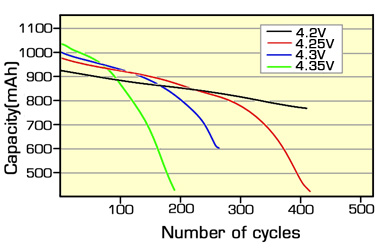

At low DOD levels such as 32 to 30 percent a lithium-ion battery can be expected to achieve between 5 and 6 times the specified cycle life of the battery which assumes complete discharge every cycle. Thus the cycle life improves dramatically if the DOD is reduced. Nickel Cadmium batteries are somewhat of an exception to this. Subjecting the battery to only partial discharges gives rise to the so called memory effect which can only be reversed by deep discharging. The cycle life of Lithium batteries can be increased by reducing the charging cut off voltage. Reducing the charging cut off voltage avoids the battery reaching its maximum stress point., similar to working at a lower DOD as in the example above. The graph below shows the typical cycle life improvements possible.The graph below displays the behaviour curve between Cycle Voltage and charge cut off voltage.

====Voltage effects====[1][3] “Rechargeable batteries each have a characteristic working voltage range associated with the particular cell chemistry employed. The practical voltage limits are a consequence of the onset of undesirable chemical reactions which take place beyond the safe working range. Once all the active chemicals have been transformed into the composition associated with a fully charged cell, forcing more electrical energy into the cell will cause it to heat up and to initiate further unwanted reactions between the chemical components breaking them down into forms which can not be recombined. Thus, attempting to charge a cell above its upper voltage limit can produce irreversible chemical reactions which can damage the cell. The increase in temperature and pressure which accompanies these events if uncontrolled could lead to rupture or explosion of the cell and the release of dangerous chemicals or fire. Similarly, discharging a cell below its recommended lower voltage limit can also result in permanent, though less dangerous, damage due to adverse chemical reactions between the active chemicals. ===Under-voltage / Over-discharge===[4] Rechargeable Lithium cells suffer from under-voltage as well as over-voltage. Allowing the cell voltage to fall below about 2 Volts by over-discharging or storage for extended periods results in progressive breakdown of the electrode materials.

Anodes

First the anode copper current collector is dissolved into the electrolyte. This increases the self discharge rate of the cell and can ultimately cause a short circuit between the electrodes.

Cathodes

Keeping the cells for prolonged periods at voltages below 2 Volts results in the gradual breakdown of the cathode over many cycles with the release of Oxygen by the Lithium Cobalt Oxide and Lithium Manganese Oxide cathodes and a consequent permanent capacity loss. With Lithium Iron Phosphate cells this can happen over a few cycles .

For example, continuously over-discharging NiMH cells by 0.2 V can result in a 40 percent loss of cycle life; and 0.3 V over-discharge of lithium-ion chemistry can result in 66 percent loss of capacity. Testing has shown that overcharging lithium cells by 0.1 V or 0.25 volts will not result in safety issues but can reduce cycle life by up to 80 percent.

Charge and discharge control are essential for preserving the life of the battery.”[4]

====Premature Death==== [1][4][2] Based on the information above, the present section contains some actions which should be considered abuse and lead batteries to failure.

“* Drawing more current than the battery was designed for or short circuiting the battery.

* “Using undersized batteries for the application”.[2]

* Circuit or system designs which subject the battery to repeated “coup de fouet” (whiplash) effects. This effect is a temporary, severe voltage drop which occurs when a heavy load is suddenly placed on the battery and is caused by the inability of the rate of the chemical action in the battery to accommodate the instantaneous demand for current.

* Operating or storing the battery in too high or too low ambient temperatures.

* Using chargers designed for charging batteries with a different cell chemistry.

* Overcharging - either to too high a voltage or for too long a period.

* Over-discharging - allowing the battery to become completely discharged.

* In aqueous batteries - allowing electrolyte level to fall below the recommended minimum.

* In aqueous batteries - topping up with tap water instead of distilled water (or inappropriate electrolyte). Subjecting the battery to excessive vibration or shock.”[4]

Internal Impedance

The internal impedance of a cell determines its current carrying capability. A low internal resistance allows high currents.

===Battery Equivalent Circuit===[1] The diagram below shows the equivalent circuit for an energy cell.

* Rm is the resistance of the metallic path through the cell including the terminals, electrodes and inter-connections.

* Rm is the resistance of the metallic path through the cell including the terminals, electrodes and inter-connections.

* Ra is the resistance of the electrochemical path including the electrolyte and the separator.

* Cb is the capacitance of the parallel plates which form the electrodes of the cell.

* Ri is the non-linear contact resistance between the plate or electrode and the electrolyte.

Typical internal resistance is in the order of milliohms.

===Effects of Internal Impedance===[1][3][4] When current flows through the cell there is an IR voltage drop across the internal resistance of the cell which decreases the terminal voltage of the cell during discharge and increases the voltage needed to charge the cell thus reducing its effective capacity as well as decreasing its charge/discharge efficiency. Higher discharge rates give rise to higher internal voltage drops which explains the lower voltage discharge curves at high C rates.

“The internal impedance is affected by the physical characteristics of the electrolyte, the smaller the granular size of the electrolyte material the lower the impedance. The grain size is controlled by the cell manufacturer in a milling process.”[3]

Spiral construction of the electrodes is often used to maximise the surface area and thus reduce internal impedance. This reduces heat generation and permits faster charge and discharge rates.

The internal resistance of a galvanic cell is temperature dependent, decreasing as the temperature rises due to the increase in electron mobility. The graph below is a typical example.

Thus the cell may be very inefficient at low temperatures but the efficiency improves at higher temperatures due to the lower internal impedance, but also to the increased rate of the chemical reactions. However the lower internal resistance unfortunately also causes the self discharge rate to increase. Furthermore, cycle life deteriorates at high temperatures. Some form of heating and cooling may be required to maintain the cell within a restricted temperature range to achieve the optimum performance in high power applications.

The internal resistance of most cell chemistries also tends to increase significantly towards the end of the discharge cycle as the active chemicals are converted to their discharged state and hence are effectively used up. This is principally responsible for the rapid drop off in cell voltage at the end of the discharge cycle.

In addition the Joule heating effect of the I2R losses in the internal resistance of the cell will cause the temperature of the cell to rise.

The voltage drop and the I2R losses may not be significant for a 1000 mAh cell powering a mobile phone but for a 100 cell 200 Ah automotive battery they can be substantial.

Operating at the C rate the voltage drop per cell will be about 0.2 volts in both cases, (slightly less for the mobile phone). The I2R loss in the mobile phone will be between 0.1 and 0.2 Watts. In the automotive battery however the voltage drop across the whole battery will be 20 Volts and I2R power loss dissipated as heat within the battery will be 40 Watts per cell or 4KW for the whole battery. This is in addition to the heat generated by the electrochemical reactions in the cells.

As a cell ages, the resistance of the electrolyte tends to increase. Aging also causes the surface of the electrodes to deteriorate and the contact resistance builds up and at the same the effective area of the plates decreases reducing its capacitance. All of these effects increase the internal impedance of the cell adversely affecting its ability to perform. Comparing the actual impedance of a cell with its impedance when it was new can be used to give a measure or representation of the age of a cell or its effective capacity.

Discharge Rates

The discharge curves for a Lithium Ion cell below show that the effective capacity of the cell is reduced if the cell is discharged at very high rates (or conversely increased with low discharge rates). This is called the capacity offset and the effect is common to most cell chemistries.

If the discharge takes place over a long period of several hours as with some high rate applications such as electric vehicles, the effective capacity of the battery can be as much as double the specified capacity at the C rate. This can be most important when dimensioning an expensive battery for high power use. The capacity of low power, consumer electronics batteries is normally specified for discharge at the C rate whereas the SAE uses the discharge over a period of 20 hours (0.05C) as the standard condition for measuring the Amphour capacity of automotive batteries. The graph below shows that the effective capacity of a deep discharge lead acid battery is almost doubled as the discharge rate is reduced from 1.0C to 0.05C. For discharge times less than one hour (High C rates) the effective capacity falls off dramatically. The effectiveness of charging is similarly influenced by the rate of charge.

====Peukert Equation====[1][4]

“The Peukert equation is a convenient way of characterising cell behaviour and of quantifying the capacity offset in mathematical terms.

This is an empirical formula which approximates how the available capacity of a battery changes according to the rate of discharge. C = (I^n)*T in which “C” is the theoretical capacity of the battery expressed in amp hours, “I” is the current, “T” is time, and “n” is the Peukert Number, a constant for the given battery. The equation shows that at higher currents, there is less available energy in the battery. The Peukert Number is directly related to the internal resistance of the battery. Higher currents mean more losses and less available capacity.”[1]

“The value of the Peukert number indicates how well a battery performs under continuous heavy currents. A value close to 1 indicates that the battery performs well; the higher the number, the more capacity is lost when the battery is discharged at high currents. The Peukert number of a battery is determined empirically. For Lead acid batteries the number is typically between 1.3 and 1.4

The graph above shows that the effective battery capacity is reduced at very high continuous discharge rates. However with intermittent use the battery has time to recover during quiescent periods when the temperature will also return towards the ambient level. Because of this potential for recovery, the capacity reduction is less and the operating efficiency is greater if the battery is used intermittently as shown by the dotted line.”[4] ====Comparison between batteries====[5] ”comparison_table.pdf”[5]

table.pdf[5]

Sources

www.wikipedia.com [1]

www.everready.com [2]

www.worley.com [3]

www.poweruk.com [4]

www.videofoundry.co.nz[5]

www.vias.org[6]